I’m a huge fan of the Judge Dredd universe (well, maybe not the Stallone film) and I love miniature skirmish games, so I I really want to like this one.

The miniatures themselves are great. The resin material Warlord Games uses strikes just the right balance between flexible and durable, and it holds a high level of detail. In the five years since the game’s initial release, Warlord have expanded the range of figures to include a pretty good cross section of characters and vehicles from the Judge Dredd comics.

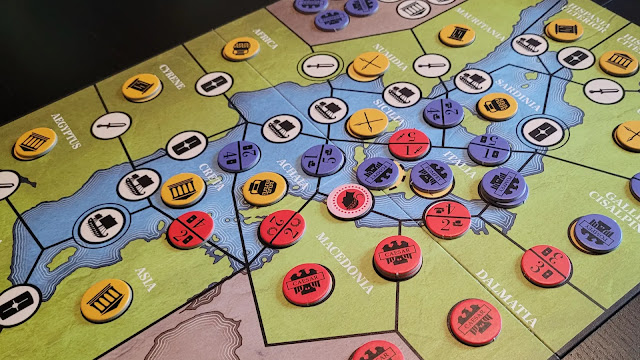

The game’s presentation is excellent. The rule book is beautifully designed, full color with a ton of artwork. The starter set comes with great looking plastic tokens rather than cardboard, plus a full color double-sided 3 foot by 3 foot map to play on. If you don’t believe me, check out OnTableTop’s unboxing videoOnTableTop’s unboxing video, it went a long way towards convincing me to buy the game.

My history with this game has been a little...conflicted. My normal pattern with miniatures games is that I get interested in a game, buy the rules and enough miniatures to try it out, and then if I like it I buy more miniatures and then either play again, or forget about the game for a year or more. That’s what happened here: I bought the Judge Dredd starter set in 2021, played several times over a period of about three months, and never played again. I seem to recall enjoying the first few games but then changing my mind, finding the last few games a little tedious and unsatisfying. So I decided to get the game and miniatures out of mothballs to make a final assessment on whether I want to continue with it or not.

The rule book, while beautiful to look at, is often vague and hard to follow. It was clearly written by someone who absolutely loves the source material, perhaps too much so. The rules are frequently bogged down in colorful descriptions of the setting and characters, what miniature gamers refer to as “fluff,” and while this sets the stage for the game, it also means that you can often find yourself wading through paragraphs of irrelevant background when trying to find a rule or clarification. It was enough of a problem that I went so far as to create a rules summary sheet to help with finding basic rules during play.

Unfortunately, my memory of the game play being a little tedious turned out to be more or less correct. The core of every skirmish game is combat between characters, so a good game needs a good system to resolve that combat. The vast majority do this via dice rolls: when my character attacks, I roll the dice, applying modifiers based on the abilities of the characters involved, and often the surrounding terrain. This can be a roll against a static target number, but in most games it’s an opposed roll, with my opponent and I both rolling the dice to see whether the attack hits or is successfully defended against.

In Judge Dredd, landing a blow is a multi-step process. First the attacker rolls, then compares the result to the target’s Cool rating to see if the target is pinned or not. Then the target rolls to see if they can dodge the attack. Then, if the target doesn’t dodge, the attacker rolls again to see how much damage is done, followed by the target rolling again to see how much of that damage they get to avoid. One attack, four rolls. Four chances to fail.

The target of the attack can come away unscathed, or pinned, and/or stunned or injured. If they’re pinned, they have to roll on their turn to see if they lose one of their two actions or not. If they’re stunned or injured, all of the six statistics that determine how far they can move and how many dice they get to roll in different situations are reduced.

Whew.

I don’t mind a complicated game if the payoff is worth it. In this case that would be an exciting story unfolding on the table, but that’s not what happened in here. Instead, the combat just seemed like a slog, and there wasn’t much else going on in the game. We played two games in a row this time around; the first game ended somewhat abruptly so we decided on a second game with more characters on each side, but towards the end we were both feeling like the game was dragging on, which brings us to my second issue with this game.

At its most basic level, a skirmish game will often come down to “everyone move to the center of the board and fight.” This can be fun, but the novelty of straight up combat wears off quickly. The best games get around this by using scenarios that introduce alternate objectives or win conditions that give players more to do than just pound the hell out of each other. It can be something entirely mechanical like controlling different geographical points on the board (Star Wars Shatterpoint does this very well), or something more story based like rescuing a captive or searching for a treasure.

The Judge Dredd rule book includes three simple scenarios, designed to introduce the game to new players using only the miniatures included in the box. Beyond that are six more that are meant to be the core of the game, offering different setups and objectives to give the game some variety. Unfortunately, these scenarios (at least the two we played, “Ambush” and “Heist”) don’t seem very well thought out. While they offer some interesting ways to start the game by starting one side in the middle rather than each side on opposite edges, the objectives for each player were uneven, making the game too easy for one player, to difficult for the other, and not much fun for either. Our first game ended really abruptly, and the other went on for so long that we called it without finishing.

The game uses cards as a way to inject variety and flavor into the game. Each player starts with a handful of “Big Meg” cards that introduce an unpredictable game effect such as a bystander stumbling into the path of the battle or a circumstance giving a free move or other action. These were sometimes fun but more often than not just annoying and egregious. In the end they didn’t make the game any better.

With the game not really working for me as-is, I am left with a few options. I could just give up on the game all together, but the miniatures are great and I love the Judge Dredd setting – I keep trying to come up with excuses to buy more of the figures even though I don’t like the game. I could try to house rule the game to get rid of its more tedious aspects. That seems like a lot of work, especially when there are so many great miniatures games out there that work fine right out of the box, but it would allow me to keep using the game’s great counters and dice. On the other hand, there are several “miniatures agnostic” games such as 7TV that allow you to use whatever miniatures you want – that seems more like the right direction to head in if I want to keep gaming in Dredd’s world.

Rating: 2 (out of 5) The game isn’t as much fun as it should be, but the fact that I can find a use for the figures without the rest of the game keeps it from being a total loss.